En 2025, Chi va piano, va TEMO.

Those who’ve been following us will know that this is the slogan of our annual campaign. Its origins lie in the Italian motto, “Chi va piano va sano e va lontano” – basically, Slow and steady wins the race.

And because the desire to

reduce our impact is part of our DNA, we’ve always sought to understand how we could

improve.

Discover TEMO's campaign : "Speed is none of our business"

One remarkable feature of our motors is how quiet they are, so the obvious characteristic to highlight was clear: what noise do they make underwater? And what impact could this have on marine wildlife?

So, we set about investigating... and discovered a world twenty thousand leagues away from the “silent world,” where sounds envelop every living thing! A study was launched, which is still ongoing, and we look forward to sharing the findings with you, probably in the fall. But it has already revealed many lessons.

The first on the list is called “Underwater Radiated Noise”! What’s that all about?

URN (Underwater Radiated Noise) is a technical term that masks a world that escapes us, yet weighs heavily beneath the ocean’s surface. Let’s start with noise, which refers to a sound that is not very harmonious: noise expresses discomfort. The fact that it’s “Radiated” is about its source: human activities. Finally, specifying “underwater” is not insignificant, as the aquatic world is another world, one in which our human references no longer apply. Underwater, light slows down before disappearing completely once you’ve gone down a hundred meters or so. In the meantime, it allows us to contemplate its varying shades of blue, the last color to be absorbed by the aquatic environment. In other words, visibility is mediocre at best! Acoustic waves, on the other hand, do not encounter the same difficulties and travel faster. Depending on their frequency, they’re capable of covering considerable distances: thousands of kilometers!

But why is underwater acoustics such an important issue?

Underwater sounds are essential to the survival of a significant part of marine biodiversity: sound is used for communication, navigation, feeding, and reproduction. In other words, it is indispensable!! Underwater, and particularly around our coastlines, there is a constant chorus known as biophony, which makes up the ambient noise. In reality, silence means the absence of life, whether on land or beneath the waves. This alarm was raised in 1962 by biologist Rachel Carson in her book Silent Spring and is now being echoed for the underwater world by the United Nations. Rising from “threat” status in 2005 to “major hazard” in 2010, underwater radiated noise is now the subject of an internationally recognized scientific consensus. It was addressed at UNOC3 (The Third United Nations Ocean Conference, which was held in Nice, France, in June 2025) with the creation of the High Ambition Coalition for a Quiet Ocean, bringing together some 37 countries. Commercial maritime traffic is the main contributor, but other human activities also play a role, such as military activities, oil exploration, and large maritime structures.

But where does recreational boating fit in among all these heavyweights?

Recreational boating is also implicated, mainly because it takes place along the coastline, an area particularly rich in biodiversity. While the noise levels emanating from recreational boating are potentially not traumatic or only slightly traumatic for marine species, they can drown out their communications.

This is known as masking, and its consequences can contribute to a lasting imbalance in an ecosystem. Indirectly, we humans are also affected: according to a 2025 OECD report, The Ocean Economy to 2050, (OECD Publishing), the ocean, which is home to 90% of terrestrial biodiversity and produces half of the oxygen we breathe, is also the main source of protein for more than 3 billion people. If the sea were a country, its economy would have been the fifth largest in the world in 2019. Between 1995 and 2020, it accounted for between 3% and 4% of global gross value added (GVA) and employed up to 133 million full-time equivalents (FTEs). Given these facts, preserving marine biodiversity is, quite simply, a matter of survival for humankind. There is no longer any doubt over the worth of reducing our underwater noise.

But where does all this noise actually come from?

Recreational boating is also implicated, mainly because it takes place along the coastline, an area particularly rich in biodiversity. While the noise levels emanating from recreational boating are potentially not traumatic or only slightly traumatic for marine species, they can drown out their communications. This is known as masking, and its consequences can contribute to a lasting imbalance in an ecosystem. Indirectly, we humans are also affected: according to a 2025 OECD report, The Ocean Economy to 2050, (OECD Publishing), the ocean, which is home to 90% of terrestrial biodiversity and produces half of the oxygen we breathe, is also the main source of protein for more than 3 billion people. If the sea were a country, its economy would have been the fifth largest in the world in 2019. Between 1995 and 2020, it accounted for between 3% and 4% of global gross value added (GVA) and employed up to 133 million full-time equivalents (FTEs). Given these facts, preserving marine biodiversity is, quite simply, a matter of survival for humankind. There is no longer any doubt over the worth of reducing our underwater noise.

Is speed a good place to look for reducing URN?

Controlling speed is a universal factor in reducing impact, not only in terms of noise but also GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions. The IMO (International Maritime Organization), which is the body that coordinates maritime regulations within the United Nations, has recognized this and has been issuing recommendations to shipowners since 2014, which were revised in 2023 through the “GloNoise” project. The issue of speed is central to this.

A trial launched in 2017 by the Port of Vancouver on a voluntary basis demonstrated the effectiveness of the measure. By asking merchant ships to reduce their speed to 11 knots in the Strait of Haro (compared to the usual 13 to 18 knots), the noise level in the area was reduced by 50%. Other positive effects included a reduction in the risk of collisions with cetaceans and GHG emissions. The operation was a real success, with 80% of shipowners responding favorably to the call.

If I slow down, do I win on all fronts?

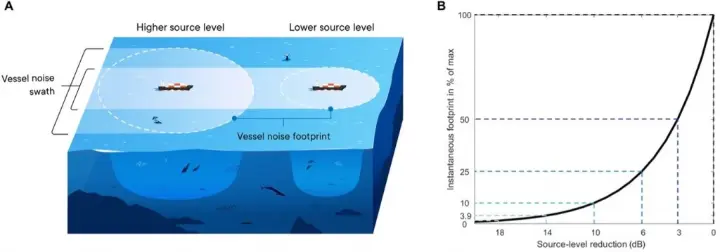

For every vessel, reducing speed also reduces the area in which this nuisance occurs, as scientists at the University of Aarhus, Denmark, have demonstrated (see figure attached).

Reducing speed also reduces ships’ energy consumption, with those “last few knots” being particularly energy intensive. According to figures from the Louis Dreyfus shipping company, reducing the speed of a bulk carrier by 2.5 knots reduces its fuel consumption and associated CO 2 emissions by 50%.

For a 150 HP outboard motor, reducing speed from 32 to 22 knots halves fuel consumption, with the best distance/fuel consumption ratio achieved at a speed of 5 knots.

For several shipowners’ associations, reducing the speed of maritime transport is the only measure immediately available that requires no investment and can massively reduce impacts (noise pollution, collisions, etc.) while meeting targets for reducing carbon emissions.

Known as “slow steaming,” it is also regularly used to control operating costs during energy crises.

How can we raise awareness of the impacts of speed?

In terms of recreational boating, in France, for example, there is already a speed limit of 5 knots in the area 300-meter from the shoreline, and other experiments are underway in certain marine protected areas in the Mediterranean. However, the scope of these experiments is too limited to effectively protect ecosystems.

Furthermore, they’re not always respected, generally not deliberately, but rather due to a lack of awareness of the real impact of speed on living organisms. As with car driving, where decades of prevention measures have led to social acceptance of lower speeds on the roads and a reduction in accidents, it is conceivable that the maritime sector will naturally undergo the same evolution. According to the insurance company April Marine, 20% of reported boating accidents involve collisions between two boats. But this also masks collisions with marine species, and these collisions are more frequent than you would think.

What is the hidden side of collisions at sea?

In maritime traffic, it is estimated that 90% of collisions with cetaceans go undetected. Yet the figures speak for themselves: estimates indicate that 20,000 to 30,000 whales die in collisions every year. Reflecting the growing awareness, institutions are introducing localized restrictions with the aim of preserving ecosystems and user safety. In the Gulf of Saint-Florent, in Corsica, the maritime prefecture has issued a decree limiting the speed of all vessels to 20 knots beyond the 300-meter zone and up to approximately 1,000 meters from the shoreline. On the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean, the “Coup de frein sur la vitesse en mer” [Slow down at sea] operation, launched in May 2024 by the local authorities, is an initiative to raise awareness of good practices at sea to protect marine animals, particularly sea turtles, which are victims of fatal collisions with boats.

France’s “Sea Turtle Observatory” is therefore calling on boaters to respect speed limits: 5 knots within 300 meters of the beach or coral reef and a maximum of 10 knots within one nautical mile. According to a scientific study, this will reduce the risk of collision by 80%.

Extend the pleasure, reduce your speed, go boating electrically: the winning combination?

Reducing your speed therefore offers a wide range of impact reduction benefits: reduced risk of collision, lower fuel consumption and associated GHG emissions, and reduced noise levels. The financial investment is zero (or even negative when you take the fuel savings into account) and the effects are immediate. The price to pay is simply the effort required to change our behavior. While recreational boating has a limited impact compared to the maritime transport sector, it has the symbolic power to positively influence public opinion and drive change across all sectors. And while technology is not a panacea, it can contribute and provide the “nudge” required to shake up our habits. With this in mind, the electrification of recreational boating can act as a game changer, as its advantages and constraints all meet the specifications required for the essential preservation of the marine environment.

How can electric motors be a game changer for recreational boating?

By design, electric motors deliver maximum torque from the moment the propeller starts to

spin. Their maximum power is available immediately and is maintained over a wide range of

speeds.

In contrast, a naturally aspirated gasoline engine (without a turbocharger) only

delivers its best torque and power at a specific speed (for example, 5,000 RPM for a

conventional outboard motor).

In a car, this problem is circumvented by the use of a gearbox that allows the engine to be used in its best range for different wheel speeds. This isn’t the case with a marine outboard motor. This makes it much less flexible to use and encourages high-speed operation, with the speed that goes with it!

The ability of electric motors to maintain high power over a wider (and lower) speed range allows propellers to be designed with greater static thrust at low speeds, pushing back the cavitation zone (and therefore noise).

Energy efficiency and suitability for our uses: Electric is ahead of the game.

While electric motors can also go fast, this comes at the cost of higher energy consumption. This is also true for internal combustion engines, which see their consumption skyrocket at high speeds. However, the energy density of gasoline, which is on average 100 times higher than that of a lithium-ion battery, compensates for this shortcoming. The difference in efficiency between the two technologies (90% for electric versus 20-30% for combustion engines) cannot bridge this gap. The arrival of solid electrolytes on the market could improve energy density, but it is fundamentally the greater energy efficiency of electric motors that will make the difference. Energy efficiency is a major challenge, and once again, speed reduction and electric technology go hand in hand to offer a credible alternative. All of the use cases associated with recreational boating also point in this direction: entering and leaving port for sailboats, navigating within the 300-meter zone, approach maneuvers, speed reduction in MPAs (Marine Protected Areas), moving around in anchorage areas, trips under motor, trolling speeds for fishing... The examples are numerous.

But first, we need to slow down!

A l’heure où l’IPBES (l’équivalent du GIEC pour la biodiversité) avertit dans son rapport Nexus, publié en 2024, que les différentes crises systémiques liées à l’eau, la nourriture, la santé et la biodiversité sont interconnectées, nous devrions raisonnablement aborder la situation en identifiant clairement les gestes les plus simples offrant une action rapide et efficace. Réduire notre vitesse sur les océans, quelles que soit nos activités, commerciales ou récréatives, en fait partie. Au moment de tourner la poignée des gaz et pour assumer pleinement notre passion pour les océans, pensons à toutes les espèces vivantes qui les peuplent, avec qui nous cohabitons, et dont dépend l’air que nous respirons. Car si la biodiversité représente autant de richesse pour l’être humain, c’est qu’il est lui-même un maillon de cette grande chaîne du vivant, aujourd’hui plus vulnérable que jamais.

So, are you ready for slow sailing?

SPEED IS NONE OF OUR BUSINESS, BIODIVERSITY IS !

This article is available in english.